We sometimes think being a child is something that happens between the ages of three and thirteen, and then it’s over. We’re no longer that child when we become the adolescent and then the adult. We read Erik Erikson’s stages of human development, and think that when we have completed the childhood tasks of trust, autonomy, initiative and competence, we leave them behind. Or we look at James Fowler’s influential stages of faith, and think that when a teenager begins to name their own belief system, they have entered the ‘synthetic-conventional’ stage, and the ‘intuitive-projective’ and ‘mythic-literal’ stages of childhood no longer have any sway in their life.

The truth is that we carry each stage with us: it remains important that as adults we attach to people with trust; that we continue to approach tasks with a sense of initiative and personal responsibility. In our faith-life, we continue as adults to find riches in the stories of our faith taken literally and simply, and continue to draw strength from the community’s understanding of God, even as we deepen our own understanding of who the Divine One is.

Hainz Streib’s Styles of Religious Development

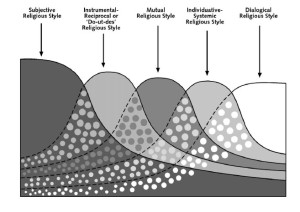

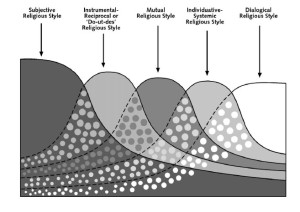

That’s why I like Heinz Streib’s ‘Styles of Development’ in which he shows how different styles of being religious dominate as we develop, but the earlier styles continue underneath – as his diagram illustrates.

Our childhood lives in our heads. In my thirties, I was a school chaplain. I deliberately remembered my feelings as a farm boy sent to boarding school to empathise with the boys in my care.

In my forties and fifties, my childhood memories crowded my dreams forcing me to make sense of my present life through the symbols of my past.

Now in my sixties, I am grandpa for four little kids and I recall my childhood to understand the dynamics of parents and children and grand-children, and work out what I can contribute to their flourishing.

If our childhood is still part of us, then we should continue to honour it. We need play. We need nurture. Who we are now is built on the foundation of our childhood, so reflection on our childhood helps us understand ourselves.

The characteristics of childhood like its openness are also vital for our relationship with God.

We need to keep being children. As if we could stop…